I met you in a landscape architecture class. I was nineteen; you couldn’t have been more than twenty. You had dark curls and chiseled features with a warmth and aura of cultivation that made you different, and I soon learned you were Venezuelan. My new housemate was an American ex-pat from Venezuela and that coincidence formed the basis of a first conversation. We became close friends. You were passionate about becoming a landscape architect; I was bouncing from one sensible major to another trying to avoid my passions. Your drive and optimism were impervious to my fragile, intellectualized self-worth. You loved unquestioningly, and you were inclined to love me but of course I was inclined to doubt the good and to seek romantic attention from more insecure partners. I floated on your surface and missed the depths.

The following year I happened to be in Venezuela on an extended stay for cultural immersion and we met up over the holidays. You showed me around Caracas, a capital city pulsing with enthusiasm and futuristic architecture situated in a bowl of mountains and lush vegetation. I remember clusters of elegant high rise apartments spilling greenery from garden terraces down pristine white walls. The country was flush with oil money. Boondoggles dotted the landscape, ambitious failed projects left abandoned with the change in government, you explained with a chagrined headshake. You pointed out the ranchitos, vast slums of multicolored shacks climbing the hillsides. This was a new and somewhat shocking sight to me. The contrast of poverty and wealth was jarring, yet here they coexisted in a kind of resigned inevitability.

We walked through a luxurious subterranean shopping mall constructed to resemble an exotic cave. From you I learned of the international chromo-kinetics movement and artists Carlos Cruz-Diez and Jesus Soto; chromosaturation rooms for immersion in color field baths, painted striped crosswalks meant to disappear over time with the passage of footsteps, and marvelous optical paintings that fooled the eye into creating illusions of color and motion. We rode an aerial tram to the top of El Avila, high in the clouds over the city where there was an eerily desolate cylindrical tower referred to as the Hotel Teleferico. As a hotel it had failed and was left standing dark and shut, another monument to impractical hubris. Fantastically, next to it was a functioning ice skating rink and on that tropical hilltop I went ice skating for the first time in my life. On the other side of El Avila the tram descended steeply through banks of clouds, hanging precariously over a jungle canopy until far, far below, meeting the edge of the blue Caribbean.

I don’t remember exactly when you transferred universities to complete an architecture degree, but I remember going to visit you not long before your graduation. We spent an afternoon walking a newly installed network of paths and boardwalks crisscrossing river wetlands. You were lively and positive as ever, brimming with dreams to continue studying in New York or Paris, to explore the world. I hadn’t seen much of you the last year or so and it struck me with a premonition of grief that I had taken a wrong turn that led to this final divergence in the path of our friendship. After that, letter writing stalled and there would be no internet or social media until far in the future to restore a connection.

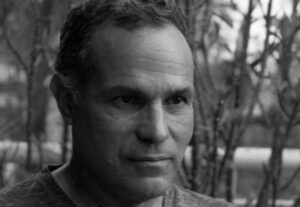

But I often thought wistfully of you, imagining you must be thriving in a European capital, at a university perhaps. Landscape architecture was a rarefied profession suited to an international metropolis, or so I thought. With the continuing unraveling and unrest in Venezuela, it seemed an unlikely place for you to end up. As years passed I only knew of Venezuelans who had fled the country. And yet, there you were. An internet search brought up a clip of you on Venezuelan TV explaining to viewers how to cultivate the natural world in their lives. You appeared the same except more distinguished with greying elegance, intently and quietly focused on work you visibly loved. You had achieved a kind of celebrity status as “the architect of Topotepuy” a stately hilltop sanctuary and education center for the preservation and diversity of indigenous plants and wildlife. You gave lectures on environmental topics such as “how to design a country like a sustainable farm according to the principles of Frederick Law Olmsted.” Knowing how unwelcome politically this could be in an OPEC country with an authoritarian government, I saw in your serenity the authentic power of fearless resistance. I felt relief at seeing you alive and well, and deep pleasure discovering how closely attuned were our philosophical paths in life.

This was never intended to be a story about tragedy. As of writing this account I haven’t yet absorbed the shock of finding out from online newspaper accounts that as of a year ago you are no longer, having been assassinated on your way home from (what else?) overseeing a sustainable farming project. That fact seems to be part of another story, a different trajectory. That fact makes sense to me less as tragedy than simply as an exclamation point at the end of a predictable narrative in a failed petrostate. (Venezuela sits on the biggest oil reserve in the world. It is also among top ten countries in biodiversity, a jaw-dropping paradise from the vast Orinoco delta in the east to snow capped Andes in the west, Caribbean beaches in the north to rainforests and savannas in the south. Due to mismanagement and corruption, Venezuela’s legendary oil industry has collapsed. Left in it’s wake is a crumbling infrastructure with daily oil spills, an unfolding environmental catastrophe. Mired in debt and desperate for cash, the Maduro government recently opened up the Orinoco Mining Arc, a swath of 12% of the country’s territory to criminal gangs associated with international mining interests. In this area are some of the most biodiverse rainforests in the world, national parks and indigenous communities. Around the world, killings of environmental activists are rising sharply, especially among indigenous populations). Whether the taking of your life was targeted or random, it had little to nothing to do with you. You knew the value of your land was in its diversity of organic life rather than its extracted oil, and you only wanted your people to share in the joy and wonder of this truth. You were killed by tacitly sanctioned organized crime in a highway roadblock near the capital of a lawless country. Like any other precious ecosystem sacrificed to a bulldozer for either extraction or development, you were simply there. In the way.

To me this story is about the respect we give our limited time on earth and our abiding love for what matters. Like Borges’ garden of forking paths, this story of our intersecting and bifurcating passages, parallels, crossings and symbols is a labyrinth in time, unspooling in seemingly random fashion with an inevitable course of destiny. Parts of the story are magical and yet it is all true.

Ricardo, eres una garza, un joropo llanero, un manantial primaveral. You moved through the world with as pure an instinct as any human could, and I am grateful and lucky to have traversed paths with you as such a remarkable friend.

.